The Solar Incentive Cliff: What the End of Tax Credits Means for Your ROI

An executive order lands on a desk in Salem, Oregon. You can almost hear the frantic sound of keyboards as state agencies scramble to obey Governor Tina Kotek’s directive to take “any and all steps necessary” to fast-track renewable energy permits. The objective is clear: get wind and solar projects into the ground before a federal deadline renders them financially nonviable.

On the surface, this is a straightforward political narrative, as detailed in reports like Oregon Fast-Tracks Renewable Energy Projects as Trump Bill Ends Tax Incentives. A Democratic governor in a green-minded state is using her executive power to counteract a hostile federal administration. The Trump administration’s “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” set a ticking clock, threatening to vaporize tax credits that can cover 30% to 50% of a project’s cost. The deadline for breaking ground is July 4, 2026. For Oregon, the stakes are quantifiable: about 4 gigawatts of planned energy, enough to power a million homes, are at risk.

This is the kind of clean, partisan conflict that generates headlines. But my analysis suggests the political theater is a dangerous distraction from the real, binding constraint. The governor’s order, while well-intentioned, is like building a pristine new on-ramp that leads directly into a permanently gridlocked, 10-lane traffic jam. The problem isn't the on-ramp; it's the highway itself.

The Anatomy of a Systemic Bottleneck

Let's look at the numbers. According to Atlas Public Policy, Oregon has 11 major wind and solar projects whose financing is now precarious. Governor Kotek’s order aims to accelerate the state-level siting and permitting process, which has been criticized as one of the country’s slowest. This is a logical, if overdue, attempt to clear a known hurdle.

The problem is that state approval is only one variable in a much more complex equation. The real gatekeeper is the Bonneville Power Administration (BPA), a federal agency that owns and operates roughly 75% of the Northwest’s high-voltage transmission lines. And those lines are, for all practical purposes, full. Getting a new project approved for interconnection—the right to plug into the grid—is a process that can take years, entirely separate from any state-level permit.

Nicole Hughes, executive director of Renewable Northwest, correctly identified this discrepancy. She noted that “even projects that already have made it through the permitting process are being held back by massive transmission queue backlogs.” This isn't a political issue that can be solved with an executive order; it's a problem of physics and decades-old infrastructure. The BPA says it's working on a "first-ready, first-served" process and expects to add about 2 gigawatts of new capacity by 2028—two years after the tax credit deadline.

This is the part of the equation that I find genuinely puzzling from a policy perspective. Why expend so much political capital on accelerating one part of a sequence when a subsequent, more critical part remains fundamentally gridlocked? Is it a case of officials wanting to be seen doing something, even if the action's material impact is questionable?

The Market's Scramble for a Plan B

When top-down policy hits a wall of physical reality, the market is forced to adapt or die. We're seeing this play out in different ways across the country, creating a fascinating, if chaotic, patchwork of survival strategies.

In Texas, for instance, installers are facing the same tax credit cliff. Bret Biggart, CEO of Freedom Solar, is essentially re-engineering his business model in real-time. His company and others are leaning into third-party ownership structures, like prepaid Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs). This is a clever form of financial arbitrage. By having a commercial entity own the residential solar system, they can access a different set of federal tax credits (including adders for domestic content) that remain available for a few more years. The math is compelling: a project that might cost a homeowner $18,000 after the tax credit in 2025 could, under a prepaid PPA, cost them only $14,000 in 2026, an approach that serves as a case study for going Beyond the Tax Credit Cliff with Freedom Solar CEO Bret Biggart. Will the average consumer understand the intricacies of a PPA versus direct ownership? That remains a significant open question.

Meanwhile, California is wrestling with a different kind of market distortion. Faced with claims that early solar adopters were overcompensated, shifting grid maintenance costs onto non-solar customers, legislators are now considering a bill that would retroactively alter those agreements. The proposed legislation would cut the benefit period for nearly 2 million customers—actually, the number is closer to 1.8 million legacy installations, but the principle stands. This move, aimed at correcting a cost shift (estimated at $8.5 billion last year alone), risks undermining the very policy certainty that encouraged adoption in the first place. It sends a chilling signal to anyone considering a long-term investment based on government incentives.

What we're witnessing is an industry in flux. In Texas, it's financial innovation. In California, it's a political battle over sunk costs. And nationally, a small interest rate cut by the Federal Reserve offers a minor bit of relief on loan costs, but it’s a gentle breeze against a gale-force headwind. These are all rational responses to an unstable and contradictory policy environment.

The Real Ledger Is Written in Copper Wire

Let’s be clear. The political maneuvering in Salem and Washington, D.C., is not the core of the story. It is a lagging indicator of a deeper, systemic failure. The fundamental constraint on America’s energy transition isn’t a lack of political will or a shortage of solar panels; it’s a shortage of transmission capacity.

The financial gymnastics in Texas and the incentive clawbacks in California are simply desperate attempts to optimize a system that is fundamentally broken at the physical layer. Governor Kotek can sign all the executive orders she wants, but her pen cannot magically create new high-voltage power lines or expedite a federal bureaucracy that operates on a timescale of years, not months. The spreadsheet that matters isn't the one tracking tax credits. It's the one tracking grid interconnection queues, and that ledger is deep in the red.

-

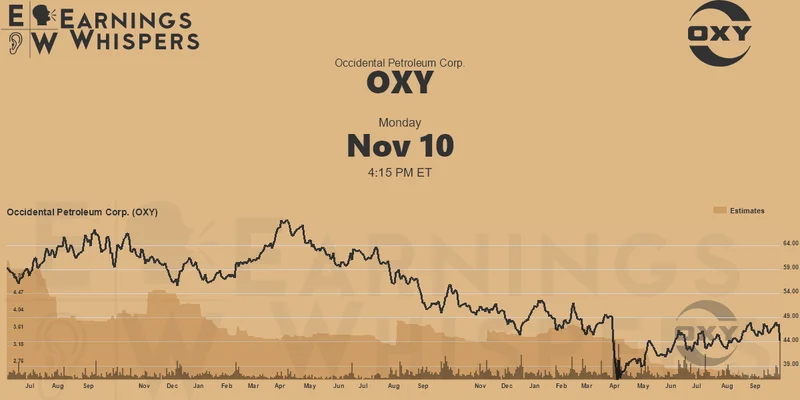

Warren Buffett's OXY Stock Play: The Latest Drama, Buffett's Angle, and Why You Shouldn't Believe the Hype

Solet'sgetthisstraight.Occide...

-

The Great Up-Leveling: What's Happening Now and How We Step Up

Haveyoueverfeltlikeyou'redri...

-

The Future of Auto Parts: How to Find Any Part Instantly and What Comes Next

Walkintoany`autoparts`store—a...

-

Applied Digital (APLD) Stock: Analyzing the Surge, Analyst Targets, and Its Real Valuation

AppliedDigital'sParabolicRise:...

-

Analyzing Robinhood: What the New Gold Card Means for its 2025 Stock Price

Robinhood's$123BillionBet:IsT...

- Search

- Recently Published

-

- DeFi Token Performance & Investor Trends Post-October Crash: what they won't tell you about investors and the bleak 2025 ahead

- Render: What it *really* is, the tech-bro hype, and that token's dubious 'value'

- APLD Stock: What's *Actually* Fueling This "Big Move"?

- Avici: The Real Meaning, Those Songs, and the 'Hell' We Ignore

- Uber Ride Demand: Cost Analysis vs. Thanksgiving Deals

- Stock Market Rollercoaster: AI Fears vs. Rate Hike Panic

- Bitcoin: The Price, The Spin, & My Take

- Asia: Its Regions, Countries, & Why Your Mental Map is Wrong

- Retirement Age: A Paradigm Shift for Your Future

- Starknet: What it is, its tokenomics, and current valuation

- Tag list

-

- Blockchain (11)

- Decentralization (5)

- Smart Contracts (4)

- Cryptocurrency (26)

- DeFi (5)

- Bitcoin (31)

- Trump (5)

- Ethereum (8)

- Pudgy Penguins (6)

- NFT (5)

- Solana (5)

- cryptocurrency (6)

- bitcoin (7)

- Plasma (5)

- Zcash (12)

- Aster (10)

- nbis stock (5)

- iren stock (5)

- crypto (7)

- ZKsync (5)

- irs stimulus checks 2025 (6)

- pi (6)

- hims stock (4)

- kimberly clark (5)

- uae (5)