Occidental Petroleum (OXY) Under Pressure: Deconstructing the OPEC+ Production News

The Chevron Discrepancy: Reading the Contradiction Between OPEC's Glut and Wall Street's Optimism

The numbers arrived without ceremony, as they always do. Another 411,000 barrels per day. That is the figure circulating from OPEC+ ahead of its October 5th meeting, representing the cartel’s next planned production increase. On its own, the number is a simple input for any supply/demand model. But it is not on its own. It is an addition to an existing, deliberate surge—a cumulative increase of more than 2.5 million barrels per day this year.

This isn't a market fluctuation; it's a strategic application of pressure. The cartel, along with its allies, accounts for roughly half of the world's oil output. When it decides to open the taps, the effect is not subtle. The stated objective is twofold: reclaim market share and placate political actors (specifically, then-President Trump) calling for lower prices at the pump. The immediate consequence is a crude price languishing below the $70 per barrel mark, a psychologically important level that delineates comfort from concern in the C-suites of Houston and San Ramon.

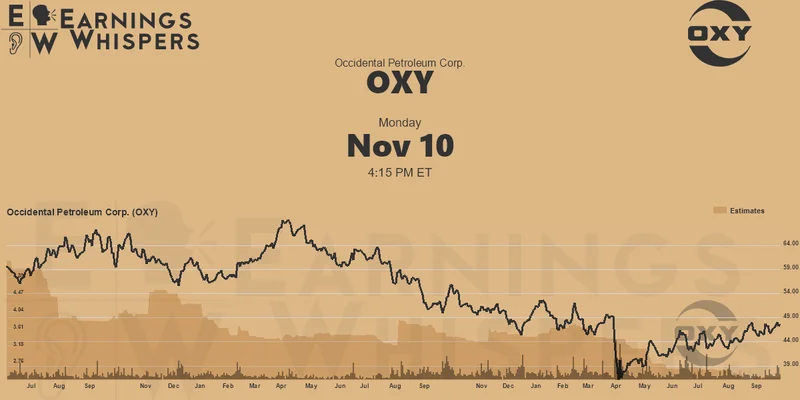

The market, predictably, is processing this data. The tickers for Chevron (CVX), Occidental (OXY), and Diamondback (FANG) are reflecting the downward pressure. This is a simple correlation, a direct and logical market response to an increase in supply. The more interesting data, however, isn't on the stock chart. It’s in the corporate filings and press releases.

A Glaring Discrepancy: When Corporate Actions Invalidate Analyst Consensus

The Operational Reality vs. The Analyst Consensus

The behavior of the oil majors themselves provides the clearest signal of their internal forecasts. These are not the actions of companies anticipating a price rebound. ExxonMobil has announced it is eliminating 2,000 jobs globally. The French major TotalEnergies is embarking on a cost-savings initiative targeting $7.5 billion over the next five years. And Chevron, the subject of our current focus, already reduced its global workforce by 20% earlier this year.

These are not trivial adjustments. A 20% staff reduction is a profound structural change, a move made in anticipation of a prolonged period of lean margins. Companies do not divest themselves of a fifth of their human capital if their internal models project a V-shaped price recovery in the next quarter. They are battening down the hatches. They are preparing for a storm, not a passing shower.

And this is the part of the report that I find genuinely puzzling. While the operational data screams caution, the Wall Street analyst consensus whispers optimism. I’ve looked at hundreds of these filings, and this particular disconnect between corporate action and analyst sentiment is unusually stark.

According to TipRanks, the consensus rating for Chevron stock among 15 Wall Street analysts is a "Moderate Buy." This rating is derived from 10 "Buy" recommendations and five "Hold" recommendations. There are zero "Sell" recommendations. Zero. In an environment where the primary commodity price is being actively suppressed by the market’s most powerful cartel and the company itself has shed a massive portion of its workforce, not a single one of these 15 analysts suggests selling the stock.

This presents a fundamental discrepancy. One of these two data sets is misleading. Either the executive teams at Chevron, Exxon, and TotalEnergies are fiscally incompetent, gutting their operations just before a price surge, or the analyst consensus is failing to properly weight the clear and present macro-level risks. My analysis suggests the latter is the more probable scenario.

Let’s deconstruct that "Moderate Buy." The average price target sits at $170.64. At the time of this data, this represents a potential upside of about 6%—to be more exact, 6.16%. A 6.16% upside is a modest return in a stable blue-chip. In a volatile commodity sector facing significant headwinds, it hardly seems to justify the risk profile. It feels less like a confident "Buy" and more like an institutional inertia, a reluctance to downgrade a behemoth like Chevron until the negative data is simply too overwhelming to ignore.

The methodological critique here is essential. How are these price targets being calculated? Often, they are based on long-term discounted cash flow models that can be slow to incorporate sudden, strategic shifts in the macro environment. A model built on assumptions from six months ago—before the full weight of the OPEC+ production increases (a volume equivalent to about 2.4% of total world demand) was felt—is now obsolete. The underlying variables have changed. The cartel is not responding to market demand; it is creating market conditions. This is a critical distinction.

The actions of the oil producers—the layoffs, the multi-billion dollar cost-cutting programs—are the most reliable leading indicators available. These are real-time, high-stakes decisions made by insiders with the most complete data sets. They are a direct reflection of the company's own, non-public revenue forecasts. To ignore these signals in favor of a 15-person analyst consensus with a lukewarm 6% upside target is to favor opinion over evidence. The numbers from the C-suite are telling a story of austerity and defense. The numbers from Wall Street are telling a story of modest, almost passive, optimism. It is not difficult to determine which data set carries more weight.

---

An Equation with a Missing Variable

The core failure of the analyst consensus on Chevron is that it treats OPEC+'s actions as a standard market variable. It is not. It is a political weapon. The current production glut is not an incidental market feature; it is a deliberate strategic choice. Analyst models built on traditional supply/demand curves are ill-equipped to price in this kind of geopolitical risk. The real-time operational data from the oil majors—the mass layoffs and capital discipline—is the only reliable signal. It indicates they are solving for a variable that the consensus "Buy" rating has failed to even include in its equation.

Reference article source:

-

Warren Buffett's OXY Stock Play: The Latest Drama, Buffett's Angle, and Why You Shouldn't Believe the Hype

Solet'sgetthisstraight.Occide...

-

The Great Up-Leveling: What's Happening Now and How We Step Up

Haveyoueverfeltlikeyou'redri...

-

The Future of Auto Parts: How to Find Any Part Instantly and What Comes Next

Walkintoany`autoparts`store—a...

-

Applied Digital (APLD) Stock: Analyzing the Surge, Analyst Targets, and Its Real Valuation

AppliedDigital'sParabolicRise:...

-

Analyzing Robinhood: What the New Gold Card Means for its 2025 Stock Price

Robinhood's$123BillionBet:IsT...

- Search

- Recently Published

-

- DeFi Token Performance & Investor Trends Post-October Crash: what they won't tell you about investors and the bleak 2025 ahead

- Render: What it *really* is, the tech-bro hype, and that token's dubious 'value'

- APLD Stock: What's *Actually* Fueling This "Big Move"?

- Avici: The Real Meaning, Those Songs, and the 'Hell' We Ignore

- Uber Ride Demand: Cost Analysis vs. Thanksgiving Deals

- Stock Market Rollercoaster: AI Fears vs. Rate Hike Panic

- Bitcoin: The Price, The Spin, & My Take

- Asia: Its Regions, Countries, & Why Your Mental Map is Wrong

- Retirement Age: A Paradigm Shift for Your Future

- Starknet: What it is, its tokenomics, and current valuation

- Tag list

-

- Blockchain (11)

- Decentralization (5)

- Smart Contracts (4)

- Cryptocurrency (26)

- DeFi (5)

- Bitcoin (31)

- Trump (5)

- Ethereum (8)

- Pudgy Penguins (6)

- NFT (5)

- Solana (5)

- cryptocurrency (6)

- bitcoin (7)

- Plasma (5)

- Zcash (12)

- Aster (10)

- nbis stock (5)

- iren stock (5)

- crypto (7)

- ZKsync (5)

- irs stimulus checks 2025 (6)

- pi (6)

- hims stock (4)

- kimberly clark (5)

- uae (5)